The Pitching

Mechanic

October 2006

Real-Time Illustrations and Analyses of

Proper and

Improper Pitching Mechanics

The

Pitching Mechanic - November 2006

10/30/2006

Adam Wainwright: More Cause

For Concern

As I have said

before, I am concerned

that Adam Wainwright of my (world champion!) Cardinals is at an

increased risk of experiencing shoulder problems, especially if he

is moved into the starting rotation next year.

The photo above from him pitching

during Game 5 of the World Series reinforces that concern. Notice

that his Pitching Arm Side (aka PAS) elbow is well above the level

of his shoulders (or

Hyperabducted). I have seen this a couple of times before, and

in both cases it was related to very serious shoulder (e.g.

Labrum) problems.

As with Joel Zumaya, this is too bad. As the photo

above shows, Adam Wainwright achieves a tremendous degree of

separation between his hips and his shoulders. Notice how his belt

buckle is facing Home Plate while his shoulder are still facing

Third Base.

10/27/2006

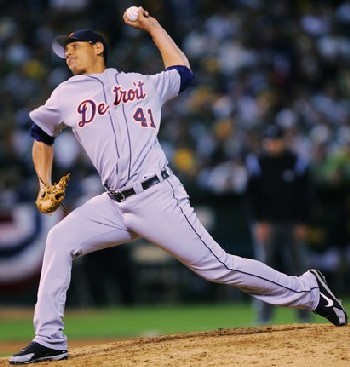

Joel Zumaya: Hips Rotating

Before Shoulders

As I have said

before, I believe that Joel Zumaya is at an increased risk for

shoulder problems, especially if he is moved into the starting

rotation next year, because he takes his elbows above and behind his

shoulders.

It's too bad, because as the

photo above shows, he does a great job of rotating his hips before his

shoulders. Notice how his belt buckle is facing Home Plate while

his shoulders are still facing Third Base. This large hip/shoulder separation helps to explain his

velocity.

10/27/2006

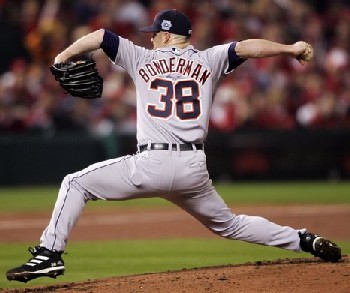

Jeremy Bonderman: Shoulder

Problems Ahead?

Jeremy Bonderman is another

pitcher that I believe faces an increased risk of shoulder

problems.

As you can see in the photo

above, taking during Game 4 of the World Series, Bonderman

Hyperabducts his PAS upper arm and takes his elbows both above and behind his

shoulders.

10/26/2006

Good Photo of Chris Carpenter

I was going over the photos from

Tuesday night's game and came across this picture of Chris

Carpenter. There are a number of interesting things to note in it.

First, you can see how Chris

Carpenter's hips rotate ahead of his shoulders. Notice how his

belt buckle is pointing toward Home Plate while his shoulders are

still facing Third Base. This will help his hips to powerfully

pull his shoulders around.

Second, you can see how Chris Carpenter doesn't really

reverse-rotate his shoulders. Instead, he strides pretty much

sideways to the target.

Third, you can see how Chris Carpenter grips his

curveball. Notice that his middle finger is sitting on one seam

and his thumb is sitting on the opposite seam.

Fourth, notice how Chris Carpenter's palm is facing

Home Plate at this point (and not Second Base). This puts his

forearm in a position of supination which will force him to

pronate his forearm in order to get his palm to face home plate. I

believe that

early pronation will help to protect his elbow by enabling his

Pronator Teres muscle to take some of the load off of his UCL.

Fifth, notice how Chris Carpenters PAS elbow is just

below the level of his shoulders. I believe that this is about the

ideal height for the PAS elbow, from both a mechanical efficiency

and injury-prevention perspective.

Finally, you can see these same things in this side

view of Chris Carpenter, which is from a slightly earlier moment

in time and in which he is also throwing a curveball.

10/25/2006

Major Leaguers and the

Marshall Pitching Motion

For those of you who, like me,

are interested in the ideas of Dr. Mike Marshall, I have added an

essay entitled

Major Leaguers and the Marshall Pitching Motion that

illustrates some of Dr. Marshall's ideas using the motions of a

number of successful major leaguers.

10/24/2006

Kenny Rogers: Crossing The

Line

After hearing about the whole

Kenny Rogers pine tar on his hand thing, I was willing to give him

the benefit of the doubt and assume that he was just trying to

improve his grip of the ball. Hey, I pitch for my over-30 slow-pitch

softball team and know that on a cold night it's extremely hard to

keep your grip on the ball on a night like that. Your fingers get

stiff and the ball gets smooth and slick.

However, while searching my

archives last night, I came across this photo from Kenny Rogers'

July 5, 2006 start. Notice that the same smudge is there on his hand at

the base of his thumb. That suggests to me that he is using the

pine tar to alter the flight of the ball, not just to improve his

grip on the ball.

It also just struck me that the reason the pine tar is

located there on his thumb is probably that his second stash is in

the pocket of his glove. The base of his thumb rubs up against the

stash in his

glove whenever he's adjusting his grip with his hand and ball in his

glove.

10/23/2006

Kenny Rogers: Look For The

Second Stash

Here's my theory about the Kenny

Rogers cheating allegations.

My

theory is that Kenny Rogers WAS cheating and the patch at the base

of his PAS thumb was his "hidden" store of pine tar. In other

words, if he got caught, he could wash it off and say he was

clean (and that of course it got there accidentally). However, he (or Pudge) had a second stash that he was

using.

You see this in the spy movies.

Someone plants a bug in an obvious place so that it

will be found. However, they also plant a second bug that is much better hidden. Once the

first bug is found, the searchers figure the problem is solved and

don't look for the second bug.

The existence of a second stash explains why Rogers' performance didn't

suffer after he was "caught".

This article suggests that his second stash could have been

hidden under the bill of his hat.

At least this whole fiasco has produced

a whole series of detailed photos of how a major league pitcher --

even if he is a cheater -- holds the ball and helps to dispel

the myth of the three point fastball grip that I discussed

below in the context of Tom Glavine. Notice that in the photo

above Rogers has a 2-Seam fastball (aka Sinker) grip, and is

gripping the lower half of the ball with both his thumb and his

ring finger, not just his thumb.

10/20/2006

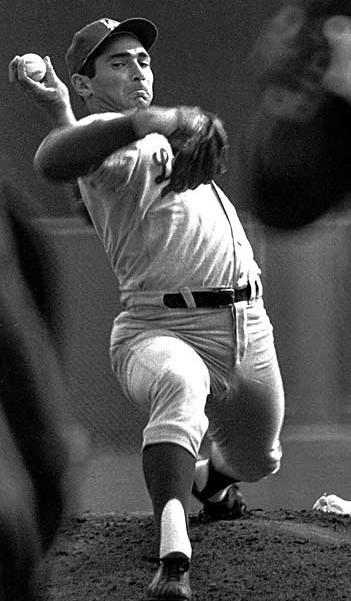

Sandy Koufax: Hips Rotating

Before Shoulders

I finally found a clean copy of

one of my favorite pictures of Sandy Koufax.

In the photo above, you can see

how Sandy Koufax's hips rotated well ahead of his shoulders.

Notice how his belt buckle is pointing toward Home Plate while his

shoulders are still facing First Base. Other things to notice are

how his Glove Side (aka GS) toe is pointing directly at the

target, how he is pulling his glove into his GS pec, and how his

GS elbow is still at the level of his shoulders (rather than down

at his side).

10/19/2006

Adam Wainwright: Uh oh...

I have been very impressed with

Adam Wainwright's performance. I especially like his curveball.

It's got that 12-6 drop that just kills hitters. That's why I am

concerned by what I see in the photo below.

It looks like Wainwright's

Pitching Arm Side elbow is both above and behind his shoulders.

Now, he admittedly doesn't

Hyperabduct his PAS elbow this as much as Aaron Heilman or

Joel Zumaya do, but nonetheless I think it is a concern. I will be

paying close attention to Wainwright's PAS shoulder, especially if

the Cardinals try to turn him into a starter next year.

10/19/2006

Aaron Heilman: Shoulder

Problems Ahead?

I was watching the game the other

night and got a chance to take a look at Aaron Heilman. I didn't

like what I saw.

Like Joel Zumaya and Billy

Wagner, Heilman

Hyperabducts his PAS elbow; he take his PAS elbow both above and

behind his shoulders. I believe that puts a tremendous amount of

strain on the rotator cuff (e.g. Subscapularis) and may lead to

injury problems in the future, especially if he comes out of the

bullpen.

10/18/2006

Beltran Perez: Good Timing

I am always on the lookout for

guys who, like Freddy Garcia, get their pitching arms up earlier

than most. I believe that doing this reduces the strain on the

shoulder.

The photo above of Beltran Perez

is an example of what this looks like. Notice how his Pitching Arm

Side forearm is vertical and in the high cocked position before

his Glove Side foot lands on the ground. Also, notice that Perez

isn't showing any signs of

Hyperabduction; his

Pitching Arm Side elbow is just below the level of his shoulders.

10/16/2006

Anthony Reyes: Tipping His

Pitches?

I was watching the Cardinals game

last night, and a couple of things struck me about Anthony Reyes.

First, I was reminded how high

Anthony Reyes' elbows get above and behind his shoulders. You

can see this clearly illustrated in the photo above that was taken

last night. I believe that this

Hyperabduction of his PAS upper arm puts a tremendous amount of strain

on his rotator cuff (e.g. Subscapularis) and calls into question

his long-term durability. I am also starting to wonder if this

problem is manifesting itself in the problems he experienced at

the end of the season (e.g. not being able to go deep into games).

Second, the commentators were talking about how Reyes

might have been tipping his pitches when he went from the Wind-Up.

While this may be the case (I wasn't really looking at this), I

wonder if a bigger problem is the differential between Anthony Reyes' two

main pitches, his fastball and his change-up. Last night

Reyes' fastball was generally coming in at 90 MPH (Low = 88 and

High = 91) and his change-up was generally coming in at 76 or 77

MPH.

As an aside, you can see Anthony Reyes' change-up grip,

which is a circle change, in the photo above.

Anyway, and as I have said elsewhere, I believe it

is best if a pitcher's change-up is 8% to 10% slower than his

fastball. There are complicated reasons, that have to do with

the perceptual thresholds of the human visual system, why I

believe this. However, suffice it to say that I believe that a

change-up that is coming in 8% to 10% slower than one's fastball

is coming in hard enough that it's not obviously a change-up, but

slow enough that it will still screw up a hitter's timing.

I don't think it's a coincidence that Greg Maddux, Jeff

Suppan, and many other effective "finesse" pitchers have

change-ups that follow this rule of thumb.

If you buy this logic, then I believe the problem

with Anthony Reyes' change-up may be that it's too slow. Given that

his fastball comes in at 90 MPH, the rule I state above would say

that his change-up should come in at somewhere around 81 or 82

MPH. However, Reyes' 76 MPH change-up is more like 15% slower than

his fastball.

Could it be that that large differential between

Anthony Reyes' fastball and his change-up makes it obvious to a

hitter which pitch is coming?

Finally, I noticed something odd about Reyes'

change-up. It didn't look like a standard change-up to me.

Instead, give how Reyes' change-up dove down near the plate, I

wonder if he's throwing kind of a hybrid between a circle change

and a curveball. Of course, the problem with hybrids (e.g. the

slurve, which is a hybrid of a slider and a curve) is that they

can end up being less effective than either pitch on its own. it

could be that Reyes' "curve-up" or "change-uvre" -- if that's

indeed what it is -- is too slow to be a good change-up and

doesn't curve enough to be a good curve.

Any thoughts? If so, then

e-mail me.

10/14/2006

Wilfredo Ledezma: Hips

Rotating Before Shoulders

I am always on the lookout for

new photos that illustrate the concepts that I teach.

The photo above of Wilfredo

Ledezma pitching in the ALCS is a great example of what the hips

rotating before the shoulders, and a large hip/shoulder

separation, looks like. Notice how his chest is pointing at 1B

(since he's a lefty) while his belt buckle is pointing at home

plate. Also, notice how the lines down the front of his uniform

curve sharply to the left.

This photo isn't quite as instructive as the

photo below of Casey Fossum (since Ledezma isn't as much of a

string bean), but it's close.

10/13/2006

Pitching Myth Busters:

The Three-Point Fastball Grip

When I first started getting into

the whole pitching thing, one piece of advice that I repeatedly

came across was that a pitcher (or a fielder) needs to have a

three-point grip on a fastball. The ball needs to be held between

just the index finger, middle finger, and thumb so as to maximize

the velocity of the ball as it comes out of the hand.

The problem is that when I tried to do this, I couldn't

get a stable grip. The kids I coached also couldn't do this since

their hands were smaller than mine.

As a result, I just resigned myself to always gripping

the ball wrong.

Well, over the past few weeks I have started collecting

pictures of how big-league pitchers actually grip the ball and

have come to see that the three-point fastball grip is overrated,

if not a complete myth.

The photo above of Tom Glavine

was taken last night and shows his 4-Seam Fastball grip. As you

can see, Glavine actually grips his 4-Seam Fastball with a

four-point grip. The ball is gripped between his index and middle

fingers on top and his thumb and ring fingers on the bottom.

You can see the same thing in the

photo above of Glavine taken just a couple of days ago. Notice how

he is gripping the bottom of the ball with both his thumb and his

ring finger.

So why are pros like Glavine able to get away with this

and not turn their fastballs into change-ups?

They are able to do this because what really matters,

in determining how fast a ball will come out of the hand, is the

amount of skin that is on top of the ball, not the amount of skin

that is under the ball.

As this photo of Jeff Suppan

demonstrates, when throwing a fastball the last thing the ball

touches are the index and middle fingers. As the wrist snaps

backwards through the release, the ball loses contact with the

fingers under the ball. As a result, they have relatively little

impact on the release speed of the ball.

That means it's perfectly acceptable to grip a fastball

with a four-point grip rather than a three-point grip.

10/12/2006

The Problem With Throwing

Sidearm

My columns below about throwing

sidearm generated a decent number of interesting questions from

readers. That includes this one from Mike G...

I was just wondering, if the arm is fully

extended out at the time of release, of which I believe also, then

is, what is considered throwing overhand any less strenuous on the

arm as throwing sidearm? I was just wondering since the tilt of

the shoulders is the only difference?

This is a great question, and let

me see if I can come up with a scientifically valid answer to it.

First, it would seem that, since the only difference

between throwing overhand and throwing sidearm is the amount of

shoulder tilt, that there shouldn't be a difference. If that was

true, then coaches shouldn't mind whether their guys threw

overhand or sidearm.

However, that doesn't seem to be that case.

The Journal of the American

Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons contains an article entitled

Shoulder and

Elbow Injuries in the Skeletally Immature Athlete in which the

authors state that pitchers who throw sidearm are three times more

likely than overhand throwers to experience injury problems.

Why would that be the case?

It appears that the root cause of the problem is that

there are distinct mechanical differences between (probably some) sidearm throwers

and overhand throwers, and those differences make throwing sidearm

riskier. For example, in an article entitled First Rib

Stress Fracture in a Sidearm Baseball Pitcher: A Case Report

the authors say...

The motion analysis of the pitching in this

case demonstrated that the sidearm style induced much more

horizontal abduction in the shoulder at the top position than

did the overhand style.

This matches up with my experience.

One of the reasons I have gotten into the whole pitching thing

is that I permanently damaged my arm when I was a kid, and I

wanted to make sure my son didn't run into the same problems. When

I was a kid, I threw from a sidearm to submarine arm slot.

What I think I did that caused my problems was that I would break

my hands high and take my PAS hand directly back toward 2B, rather

than taking my PAS hand down, out, and then up. Then, as my hand

was still moving back toward 2B, I would start rotating my

shoulders. This allowed me to get a lot on the ball, but it also

put a tremendous amount of stress on my shoulder as it experienced

a larger than average amount of adduction (aka horizontal

abduction).

So what's the bottom line?

While it may be possible for a pitcher to throw safely

from a sidearm arm slot, coaches have to be very careful to ensure

that pitchers break their hands properly. That means swinging the

pitching arm down, out, and then up and into the Ready position

and not picking up the forearm and taking it up and back to the

Ready position.

10/11/2006

Pitching Myth Busters:

Arm Slot - Perception vs. Reality

Yesterday at lunch I had a

conversation with a guy who has written a number of books about

sports (one of which was given to my son). Some of the things he

said didn't ring true with me, so I decided to take a look at the

book my son was given.

Arm Slot: Perception

In the book, I found a diagram

very much like the one above that tried to explain the differences

between the arm slots that pitchers throw from. This diagram

suggests that the difference between arm slots is how much the

pitcher's elbow is bent as they release the ball. It explains that

a sidearm pitcher's elbow is fully extended at the release point

while an overhand pitcher's elbow is bent 90 degrees.

The problem is that, when you are talking about kids

who are older than 10 or so, THIS IS WRONG!

Arm Slot: Reality

The reality is that, due to the

forces involved, every pitcher's elbow is fully extended at the

release point. The thing that determines their arm slot is

how much their shoulders are tilted.

Why, you ask, is this a big deal?

It's a big deal because how can you trust the advice of

someone who doesn't understand what the arm actually does during

the throw? Some of what they say is based on a misconception of

the throwing motion, and some of their advice may be wrong (if not

dangerous).

Of course, this common misconception can be used to

evaluate potential pitching coaches. By asking them what the arm

does, and how much the elbow is bent, through the release point

you can quickly determine who knows what they are talking about

and who doesn't.

10/5/2006

Pitching Myth Busters:

Rapid Internal Rotation of the Upper Arm

is an Important Source of Power

If you read the technical (e.g.

medical) literature about baseball pitching, one statistic that

you will frequently come across is that much of a pitcher's power

results from the rapid internal rotation of the upper arm (e.g.

Humerus). Some people believe that a pitcher's upper arm

internally rotates up to 7000 degrees per second. I was

immediately skeptical about this claim when I first came across

it, and believe that it is wrong. Let me use the photo below of

Pedro Martinez to explain my skepticism.

I believe the photo above blows a

hole in the idea that the rapid internal rotation of the upper arm

is responsible for much of a pitcher's power. Notice that in the

photo above, Pedro Martinez's upper arm is still externally

rotated (his palm is facing up). It is impossible for the rapid

internal rotation of his upper arm to generate much power, because

his elbow is extended and as a result his hand is pretty much on

the axis of rotation.

Try putting your arm in this position and see how much

you can get on the ball.

I doubt if it's very much.

I believe that the idea that the rapid internal

rotation of the upper arm is responsible for much of a pitcher's

power is based on a fallacy; that a pitcher's elbow is bent 90

degrees at the moment that the rapid internal rotation of the

upper arm occurs. I grant you that, in that case your could get

something on the ball because the ball would be the length of the

forearm from the axis of rotation.

However, the above photo makes it clear that the elbow

is not bent 90 degrees at the moment that the rapid internal

rotation of the upper arm occurs. Instead, the elbow is fully

extended at this moment.

So what is the primary source of a pitcher's power?

As I have said before, and as

this photo of Pedro Martinez illustrates, it's the rotation of the

hips before the shoulders. This stretches the muscles of the torso

and enables them to powerfully the the shoulders around.

10/5/2006

Pitching Myth Busters:

The Myth of Arm Slot

When it comes to pitching, people

are always talking about arm slot, how it's genetic, and how you

shouldn't try to change it.

I think that's garbage.

The thing that makes Pedro

Martinez throw from a sidearm arm slot is that he doesn't tilt his

shoulders as they are pulled around by his torso.

In contrast, the thing that makes

Tom Glavine throw from a 3/4 arm slot that he tilts his shoulders

roughly 45 degrees as his shoulders come around.

It's that simple.

10/1/2006

Look At All The Knuckle

Curves!

I believe that a knuckle

curveball (aka knuckle curve) is the best kind of curveball for a

young pitcher to throw. This is because it is thrown like a

fastball and the topspin comes from the rapid extension of the

index finger rather than the twisting of the wrist or forearm.

I used to think that major league pitchers who threw

the knuckle curve were few and far between, but in the past few

days I have come across a number of photos of big league pitchers

throwing the knuckle curve.

Above are four photos of Mike

Mussina throwing his knuckle curve.

Here's a photo of Bobby Jenks of

the White Sox throwing a knuckle curve.

Here's a photo of Danny Haren of

the A's throwing a knuckle curve.

Here's a photo of Dustin Moseley

of the Angels throwing a knuckle curve.

The

Pitching Mechanic - September 2006

|